Since 1945, Britain’s two dominant parties – Labour and the Conservatives – have each presided over policies that cumulatively hollowed out the nation’s industrial base, undermined key services, and eroded global standing. This analysis chronicles how successive governments, instead of safeguarding Britain’s future, often indulged in short-sighted political fixes. From the mythologised birth of the NHS to the near-collapse of coal, steel, and shipbuilding, and from union-pandering pay deals to stagnant defence budgets, both Labour and Conservative administrations share blame for Britain’s post-war decline. Drawing on historical data and academic research, we critically examine major policy choices – nationalisations, funding decisions, and (in)actions, and their dire long-term consequences. The picture that emerges is one of bipartisan mismanagement, wherein lofty promises masked structural damage that subsequent governments proved either unwilling or unable to reverse.

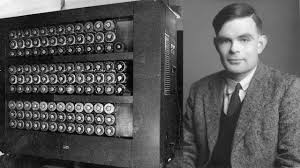

1936: Alan Turing & The Turing Machine, the world’s first electronic computer.

The Technological Betrayal – Britain’s Surrender of the Digital Future

Amid Britain’s industrial and geopolitical decline post-1945, one of the most damaging – and least discussed, betrayals was the government’s catastrophic failure to recognise and invest in the emerging technological revolution it had helped to spark. During the war, Britain was home to some of the greatest scientific minds of the era and the birthplace of revolutionary advancements in computing, radar, cryptography, and aerospace. But the political class, lacking vision and strategic understanding, not only failed to capitalise on these breakthroughs, but they also actively destroyed them or handed them over to foreign powers.

The clearest example of this is the story of Alan Turing and the Colossus computers. Turing’s wartime work on the Bombe machine and his pioneering research into logic and machine intelligence laid the groundwork for modern computing. Meanwhile, the Colossus, developed at Bletchley Park by Tommy Flowers, was the world’s first programmable, electronic digital computer. Ten were built and operated in secret to crack German Enigma codes faster than ever before. Yet after the war, these achievements were buried in secrecy. Under a Labour government obsessed with post-war reconstruction and diplomatic appeasement, the Colossus machines were dismantled and their designs ordered destroyed. Turing’s own post-war proposals to integrate computing into national infrastructure, particularly the telephone system and scientific research, were ignored. Rather than lead the digital age, Britain turned its back on it.

Turing, one of the few true geniuses of the 20th century, was hounded by the very state he helped save. In 1952, he was convicted of ‘gross indecency’ for being homosexual – an act of state persecution that led to his chemical castration and ultimately his early and avoidable death by his own hand in 1954. His prosecution not only ended his career but also silenced one of the few voices who understood where computing was going and what it could do for Britain. The intellectual leadership he could have provided to British science and engineering was lost, not by accident, but by deliberate institutional cruelty.

Meanwhile, the United States, which had trailed Britain in wartime computing, benefited from Britain’s technological naivety. Turing’s methods, British advances in cryptography, and the architecture of Colossus were handed over and replicated across the Atlantic. Companies like IBM capitalised on ideas Britain had pioneered. The US built a computing industry that would dominate the global economy by the 1980s, while Britain lagged behind, a client state rather than a leader.

Sir Frank Whittle and the Jet Engine he invented

It is also crucial to note that the RAF had, began development of before, but perfected during, the war, an information-sharing system that foreshadowed the modern internet. Britain’s integrated air defence network, combining radar stations, radio communications, teletype links, command and control centres, trained aircraft spotters and anti-aircraft emplacements coupled with visual data plotting, functioned as a decentralised, fault-resilient, or as fault resilient as technology allowed at the time, early warning and robust communications grid.

It was, in essence, an analogue version of the internet. Had Britain followed Turing’s lead and begun digitising and automating that infrastructure during and especially, post-war, the UK could have become the world’s pioneer in internet and networked technologies decades before ARPANET. The technological seeds were there, the researchers and technologists had the vision, but the stuffy old men who held the purse strings and decision-making power simply ignored their vision.

Instead, short-term politics and a criminal lack of vision saw the country squander its lead. The destruction of Colossus, the persecution of Turing, and the giveaway of scientific breakthroughs meant that Britain entered the second half of the 20th century with none of the technological momentum it should have had. The economic consequences were profound. The computing and digital industries, which became the foundation of global economic dominance in the US, Japan, and later China, were not British led, even though they could, and should, have been. Tens of thousands of high-skill jobs, £billions in potential revenue, and a strategic edge in communications, cryptography, and data science were all lost to short-sighted mismanagement.

This betrayal, rooted in the late 1940s and early 1950s, is one of the great tragedies of modern British history. It was not inevitable. It was political. And it must be remembered, not as a footnote in wartime achievement, but as a decisive fork in the road where Britain turned away from its own future. The Labour Party betrayed the British People in 1945 in a way not far short of treason, they sold the nation’s long-term future for short term political expediency. The Labour Party has never worked in the nation’s best interests, although as we shall see, they were not alone in this epic failing. It should be recalled that many advances Britain had made before the War were also exchanged with the USA as part of the Tizzard Project as a way of using US manufacturing resources to realise or improve output on many projects, this included Frank Whittle’s Jet Engine, the Cavity Magnetron, Superchargers as well as the Frisch–Peierls memorandum and MAUD Report describing the feasibility of an atomic bomb, which was used as a basis for the Manhattan Project – the massive undertaking in the remote New Mexico desert that saw the creation of The Fat Man and Little Boy devices used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945

The NHS Creation Myth: Coalition Vision, Labour Appropriation

Perhaps no institution is as fiercely claimed by Labour as the National Health Service. Generations have been taught to credit Labour’s Clement Attlee and Aneurin “Nye” Bevan as the sole architects of the NHS. Labour’s official history hails the 1948 NHS launch as the party’s proudest achievement, asserting bluntly that “Labour created the NHS” (Labour claims credit for the NHS, but Liberals laid the foundations). Yet this popular narrative is a distortion of history – one that conveniently omits the pivotal role of non-Labour visionaries and the wartime coalition government.

In truth, the blueprint for a universal, tax-funded health service predated Labour’s post-war government. Sir William Beveridge’s 1942 report – commissioned by Churchill’s wartime coalition – first articulated the idea of a “National Health Service” as part of a broader welfare plan (Labour claims credit for the NHS, but Liberals laid the foundations) (Labour claims credit for the NHS, but Liberals laid the foundations). All major parties endorsed Beveridge’s proposals during the 1945 election (Labour claims credit for the NHS, but Liberals laid the foundations), reflecting a rare post-war consensus. Moreover, Churchill’s coalition took concrete steps: Conservative Health Minister Sir Henry Willink authored a 1944 White Paper outlining a free, comprehensive health service (Profile: Henry Willink, the Conservative who proposed a National Health Service before Bevan created one | Conservative Home) .

Willink even appeared on newsreels in 1944 to announce that “whatever your income, if you want to use the service… there’ll be no charge for treatment” – an NHS in all but name. As Churchill declared in March 1944, “our policy is to create a national health service” accessible to all. These commitments were made while Attlee was still a junior partner in coalition, not yet in power. Commitments during wartime prevented the allocation of the resources, both financial and human, to realise the idea before the end of the war, although Labour like to ignore that little slice of true history.

Labour did indeed implement the NHS in 1948, for which Bevan and Attlee deserve credit. But Labour’s later claims to exclusive parentage of the NHS are ahistorical and self-serving. Historians note that Bevan himself gradually encouraged the myth of sole Labour creation, especially after he resigned from government in 1951, “representing the Health Service as his personal creation” as a political tool (Profile: Henry Willink, the Conservative who proposed a National Health Service before Bevan created one | Conservative Home). This mythology obscures the “long and cumulative process” by which the NHS actually came into being. In reality, “some form of National Health Service would have come into being after 1945 whoever had won the General Election”. The Conservatives under Churchill not only supported the NHS plan but had helped design it – a fact often airbrushed out. Indeed, the first NHS Bill presented in 1946 built on Willink’s earlier proposals, and when Bevan chose a more radical path (nationalizing all hospitals outright), Willink objected only to how the NHS was organised, not whether it should exist. For their trouble, the Tories earned a lasting (and false) reputation of being “lukewarm” on the NHS.

Over the years, Labour’s partisan retelling hardened into gospel, overshadowing contributors like Beveridge (a Liberal) and Willink (a Conservative). “The role of the Conservatives… in the development of the NHS is today entirely forgotten”, laments one historian. It serves Labour’s interest to misrepresent the NHS’s origin, wrapping the service in a red flag and casting opponents as eternal NHS bogeymen. But as archival evidence and historians such as Nicholas Timmins and Paul Addison have shown, the welfare state, including the NHS, was fundamentally a cross-party project (Labour claims credit for the NHS, but Liberals laid the foundations). Labour has repeatedly ignored this inconvenient truth to claim a monopoly on NHS virtue – a strategy that is politically useful, but intellectually disingenuous.

Nationalisation – Labour’s Economic Folly and Lingering Damage

If Labour’s NHS tale is one of exaggerating its own genius, its mid-century economic policies show the opposite – a hubristic interventionism whose ill effects haunt Britain to this day. Upon winning the 1945 election, Attlee’s Labour government embarked on an unprecedented wave of nationalisations, powered by the socialist belief, enshrined in Labour’s 1918 Clause IV, that “common ownership of the means of production” was an inherently good end. In a dizzying six-year span, Labour swept major industries into state ownership, including coal, railways, iron and steel, gas, electricity, inland waterways, aviation, and banking.

By 1951, the commanding heights of Britain’s economy were monopolised by government-run corporations. Though wartime state control made nationalisation seem a natural evolution, these moves were ideologically driven, Labour’s chance to fulfil its socialist program on a grand scale.

Initial justifications for nationalisation ranged from rational economic planning to saving war-worn industries. Indeed, some sectors needed restructuring – the railways had been battered by war and competition from road transport, coal mining was plagued by antiquated pits and poor labour conditions. Centralising these under public boards, it was argued, could coordinate investment and improve efficiency (Nationalisation).

However, whatever short-term stability nationalisation provided was soon outweighed by long-term stagnation and inefficiency. Freed from market competition and profit discipline, the new state industries became bloated, unresponsive monopolies. By the late 1970s, Britain’s nationalised giants were synonymous with low productivity, chronic losses, Union extremism and outdated practices.

Several structural problems afflicted these industries from the outset. Managers of nationalised companies were “not required to meet any efficiency objectives” – there were no shareholders or profit motive to enforce discipline (Nationalisation). Protected from competition, state-owned businesses grew “X-inefficient”, incurring high costs for low output (Nationalisation). When losses inevitably mounted, governments reflexively covered them with subsidies, creating a moral hazard, executives knew the taxpayer would always bail them out (Nationalisation). This cycle encouraged complacency and under-investment, given finite public funds, industries had to compete with schools, hospitals, and defence for capital, resulting in “a prolonged period of under-investment” in modernising plant and equipment (Nationalisation).

Industrial stagnation was rife and getting worse.

Political interference further compounded inefficiencies. Governments used state firms as tools of social policy, often at odds with commercial logic. At various times, ministers pressured nationalised industries to hold down prices, in order to fight inflation, or avoid layoffs, to fight unemployment, regardless of the cost to both the economy and nation. Investment decisions were driven by political expediency – e.g. siting new factories in high-unemployment areas rather than where they’d be most productive. Unions, seeing the state as a soft target, leveraged their clout to resist closures or technological changes that might threaten jobs. Managers often opted for a “quiet life” instead of contentious reforms, knowing that pushing efficiency could provoke strikes or political blowback. The result was overstaffing and ossification, by the 1970s Britain’s nationalised industries were grossly uncompetitive compared to foreign rivals.

Labour’s nationalisation spree thus sowed the seeds of industrial decay. Coal mining provides a stark example. When Attlee’s government created the National Coal Board (NCB) in 1947, there were 1,503 collieries (coal mines) in operation in the UK, of which 958 were nationalised by the Labour Government, 400 were left in private hands, 1,334 were deep mines and 92 were surface mines, the total workforce was over 804,000 with 711,000 miners coming under state control (20 Year Review of the Coal Industry 1947-1967).

The NCB initially aimed to modernise coal output, but political priorities shifted toward subsidising employment and keeping uneconomic pits open. As cheaper oil and gas emerged and coal demand fell, the British coal industry should have contracted – instead, successive governments propped it up far too long. Paradoxically, this only made the eventual collapse more painful, a point we examine in detail later.

Similar patterns played out in steel and rail, Labour’s creation of the British Steel Corporation (BSC) in 1967 came after two decades of flip-flopping (Attlee nationalised steel in 1950, the Tories privatised it in 1953, Labour renationalised in 1967) that left the industry starved of capital and direction (British Steel (1967–1999) – Wikipedia).

By the 1970s, BSC’s plant was obsolete and its productivity abysmal, yet the Labour government’s overriding goal was to “keep employment high” at British Steel, especially in depressed regions (British Steel (1967–1999) – Wikipedia). Mills were kept running at a loss to avoid layoffs, an unsustainable policy that delayed an inevitable and catastrophic reckoning.

In short, Labour’s post-war socialist economics, however well-intended, were poorly thought through and held no economic merit, as a result they inflicted long-term damage to Britain’s competitiveness and productivity. Nationalisation created state-run behemoths that became bywords for inefficiency, draining the Treasury and falling behind international peers. A comprehensive review in 1979 found the record of the 1970s nationalised industries “unfavourable… on key measures including labour productivity, output growth and return on capital” compared to the private sector. Far from harnessing the “commanding heights” for national prosperity, public ownership often institutionalised mediocrity. By 1979, Britain faced an economy laden with uncompetitive state enterprises – a grim legacy of Labour’s socialist and illconceived structural missteps.

Industrial Decline in Data – Coal, Steel, Shipbuilding and More (1945–Present)

Nothing illustrates Britain’s managed decline better than the employment freefall in its major industries. In the early post-war decades, millions laboured in coal mines, steel mills, shipyards, and factories. Today, only vestiges remain. The following sections chart these trends with hard data, showing year by year how many jobs were lost, and under whose government watch, indicated by red for Labour and blue for Conservative periods in the graphs.

The Coal Industry – From Nationalisation to Near-Extinction

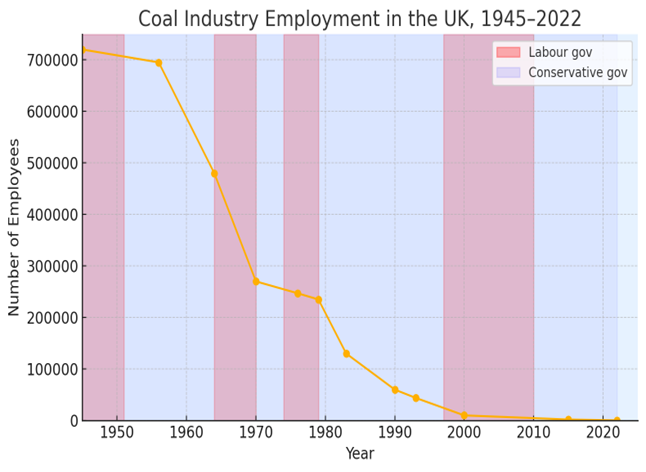

Figure 1: Coal Industry Employment in the UK, 1945–2022. Red zones = Labour governments; Blue = Conservative. Employment fell from ~700,000 miners in the late 1940s to essentially zero by the 2020s.

At the end of WWII, coal was king, employing roughly 804,000 Britons and powering an industrial nation. But over the next 75 years, UK coal mining all but vanished. Total coal mining jobs collapsed from 704,000 in 1956 to 247,000 by 1976, and just 44,000 by 1993 (Coal mining in the United Kingdom – Wikipedia). The graph in Figure 1 underscores the steepest declines. Notably, huge workforce reductions occurred under both parties. In fact, contrary to common belief, more coal jobs were lost under Labour governments than under Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives. During Harold Wilson’s 1964–1970 Labour tenure, 212,000 mining jobs were eliminated, a ~48% drop.

This single six-year period saw the coal workforce shrink from roughly ~517,000 to ~270,000 – a drop of 247,000 Jobs. By comparison, during Mrs. Thatcher’s 1979–1990 term, mining employment may have fallen by ~80% in relative terms – roughly 180,000 jobs lost, from ~235,000 miners to under 50,000. In absolute numbers, Wilson’s government oversaw the bigger purge (247,000 jobs gone). The oft-repeated trope that Thatcher “destroyed the coal industry” overlooks the ongoing decline already well underway in the 1960s and ’70s, which was encouraged and endorsed by Labour when in Office.

Why did Labour preside over such a massive contraction of coal? Largely because market forces and technology were inexorable, the least efficient pits closed as oil, gas, and imported coal gained favour. Wilson’s government recognised by the mid-1960s that the coal industry had to be “pruned” – indeed, Labour was quietly shutting mines at an even faster rate than Thatcher later did (Tory spin on coal masks fact that 80 per cent of coal jobs were lost under Thatcher – Left Foot Forward: Leading the UK’s progressive debate). Yet Labour simultaneously maintained a public narrative of solidarity with miners, even as it axed their jobs at an ever-increasing rate, with little or not support, behind the scenes. By 1974, after two decades of closures under both parties, Britain’s coal labour force had dwindled to 244,954, down from 724,000 in 1948 (20 Year Review of the Coal Industry 1947-1967). (Hansard)

In other words, nearly 67% of coal mining jobs disappeared before Thatcher even took office.

The Thatcher government’s confrontation with the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) in 1984–85, culminating in the defeat of the miners’ strike and an accelerated pit closure program, is often portrayed as an unprecedented assault on coal communities, but the data shows it was the culmination of a decline long in motion. Between 1980 and 1994 (spanning Thatcher and John Major’s years), over 200,000 miners were displaced, a 90% workforce reduction (Job displacement costs of phasing out coal) (Job displacement costs of phasing out coal). This was brutal, but one must ask – what was the alternative by then?

The industry had been kept afloat through heavy subsidies and deferment of tough choices, especially under 1974–79 Labour, which preferred to pay miners to keep mines open. When Thatcher cut those subsidies, because it made no economic sense, the industry’s artificial life support ended, and the remaining jobs went into freefall.

It should be noted that the nationalised energy generation industry had been encouraged, by the same governments, especially Labour, to import cheap coal from Germany and Eastern Europe, which undermined efforts to keep the British mining industry alive rather than on artificial life support.

Chart created with Data from Historical coal data: coal production, availability and consumption 1853 to 2023

An International Energy Agency study notes that one-third of all UK mines closed in just 1985–86 after the strike, as the government withdrew support (Job displacement costs of phasing out coal). Several of the closures were due to the mines becoming flooded due to the mineworkers’ pickets preventing engineers from entering the mines to maintain them.

Regardless of the reason for the closure, however, the human cost was immense, mining communities suffered “large and persistent earnings losses” and social dislocation (Job displacement costs of phasing out coal). But crucially, the hardship did not start with Thatcher, it started in the 1960s and 70s, under governments, especially Labour, that talked up coal while quietly abandoning its future. They robbed Peter to pay Paul without considering the long term impact this would have.

In summary, Britain’s coal industry story is not simply one of Thatcherite villainy. It is one of decades of mismanagement by all, leaving an industry so uncompetitive that it collapsed under its own weight. Labour’s nationalisation did not save King Coal, it only delayed it’s the inevitable and arguably made the eventual collapse even harder impacting by the 1980s.

By 2020, only a few hundred coal miners remained employed in the UK (Coal mining in the United Kingdom – Wikipedia).In the last few years, even those jobs have been lost, and now the UK Coal mining industry is all but gone. It is telling that by the time Thatcher came to power, British coal mining had already fallen 81% from its peak of 1.2 million in 1920 down to ~235,000 by 1979) (Coal communities and the demonisation of Thatcher and Obama).

Both parties presided over the decline – neither found a way to truly resuscitate coal regions once the economic logic for mining was gone.

The Steel Industry: “Saving Jobs” vs. Saving the Industry

Britain’s steel sector illustrates a similar trajectory, post-war dominance followed by relentless shrinkage. In 1950, Britain produced 16 million tons of steel, a world leader. The workforce was large and unionised. But like coal, steel became a casualty of Labour’s nationalisation and failure to modernise, followed by Conservative inaction until collapse was unavoidable. The same mismanagement and radical union actions doomed the industry.

When Labour renationalised steel in 1967 under BSC, the industry employed roughly 250,000 workers. Instead of rationalizing capacity and investing in new technology (as German and Japanese steelmakers did), BSC under political direction chose to maintain redundant plants to avoid layoffs (British Steel (1967–1999) – Wikipedia). By the mid-1970s, BSC was running huge losses – yet Labour ministers instructed it to keep open “uneconomic” mills in regions like Scotland and South Wales for social reasons (British Steel (1967–1999) – Wikipedia). The result was that by 1977–78, British Steel was non-competitive and haemorrhaging money. In 1977 alone, BSC lost £145 million (Updated: The British steel industry since the 1970s – Office for National Statistics) (nearly £800 million in today’s money), prompting an urgent need for reform.

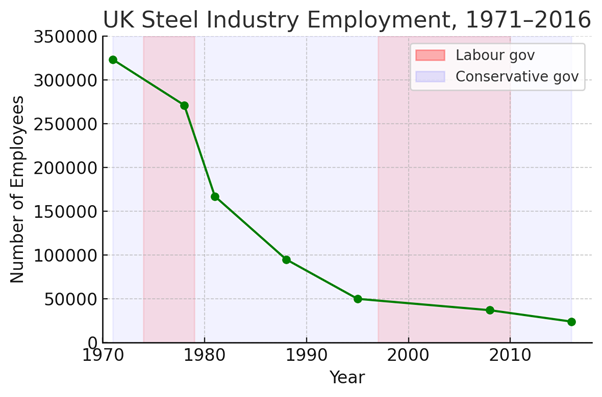

Figure 2: UK Steel Industry Employment, 1971–2016. Red = Labour government; Blue = Conservative. Employment fell from over 320,000 in 1971 to under 25,000 by 2016 (Unions review links with ‘new Labour’ | European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions).

Figure 2 shows the drastic headcount reduction that followed. The late 1970s and early 1980s were devastating for steel jobs. Employment plunged from 271,000 in 1978 to 167,000 by 1981 (Updated: The British steel industry since the 1970s – Office for National Statistics) (Updated: The British steel industry since the 1970s – Office for National Statistics) – a drop of over 100,000 jobs in just three years. This was under a mix of governments – the tail end of Jim Callaghan’s Labour and the beginning of Thatcher’s term. Notably, the single biggest fall occurred 1978–81, the period of the infamous 1980 steel strike and subsequent restructuring. (Updated: The British steel industry since the 1970s – Office for National Statistics).

These were years of national strikes and plant closures as BSC belatedly tried to shed excess capacity. The Thatcher government, unlike her predecessors, was willing to bite the bullet. Under Sir Ian MacGregor’s chairmanship, BSC slashed its workforce and closed inefficient works to return to profitability in the 1980s. By 1988, steel employment had fallen below 100,000 for the first time (Updated: The British steel industry since the 1970s – Office for National Statistics).

While this drastic slimming eventually made British Steel productive again, it was reprivatised in 1988 and soon became one of Europe’s most efficient steelmakers, the social cost was enormous. Labour had prioritised “saving jobs” in steel, but by postponing necessary restructuring, it arguably increased the ultimate job losses. As one historian noted, Labour in the ’70s kept mills open “at a loss” to avoid unemployment (British Steel (1967–1999) – Wikipedia), leaving BSC with antiquated assets and inflated payroll. When the reckoning came under Thatcher, it had to be that much fiercer. Thus, over 100,00 steelworkers were made redundant in a short span, and entire towns, such as Consett & Corby, were devastated when their steelworks closed around 1980.

From 1988 onward, the steel workforce continued to decline gradually, mirroring global trends of automation and productivity gains. By 2014, the UK steel industry employed only 34,500 people (Updated: The British steel industry since the 1970s – Office for National Statistics), and by 2016 around 24,000 (32000 people work in the British steel industry – Full Fact) – less than 10% of its size in the early 1970s.

Once again, what began as a Labour attempt to “run the industry for the people” ended with an even more severe collapse later. In an ironic twist, British Steel in private hands, after 1988, performed far better, boosting output per worker and even turning profits, but only by shedding the bulk of its workforce and modernising aggressively. The long-term damage of the earlier mismanagement was the loss of Britain’s status as a major steel producer. British Steel eventually merged into a Dutch company in 1999, investment in the 2000-1006 period was fierce, but it did not help the ultimate decline, and today Britain produces only a fraction of the steel it did in 1970 and is Chinese owned but has just been bailed out by the Labour Government in Stockport where the owners were running the plant into the ground because it is uneconomical and requires too much investment to remain competitive, thus, current Labour are simply repeating the mistakes of their past.

Shipbuilding, the Merchant Marine and Fishing – The Vanishing Seafarer Jobs

Britain’s decline as an industrial power is perhaps most evident in shipbuilding, merchant marine and fishing, three sectors intertwined with the nation’s maritime heritage.

Shipbuilding

In 1950, Britain still launched more ships (by tonnage) than any other country, commanding a third of the world market (EEBH_2007003). Yards on the Clyde, Tyne, Wear, and Belfast were major employers. Yet by 1980, British shipbuilding was a shadow of its former self – undercut by Japanese and Korean competition and hamstrung by its failure to modernise. Successive governments poured money into rescue schemes, creating British Shipbuilders as a national corporation in 1977 under Labour, but with little success. The modernisation that was required, that we saw take place in Norway and France, did not materialise, money was invested poorly and in the wrong way.

When British Shipbuilders was formed, 45,200 workers were employed in merchant shipbuilding (1977) (British Shipbuilders (Hansard, 14 December 1988)). A mere decade later, only 11,300 remained (1987) (British Shipbuilders (Hansard, 14 December 1988)). In other words, three-quarters of shipyard jobs vanished in ten years. This happened largely under a Labour government, in the late 1970s, which kept failing yards on life support, followed by Thatcher’s government, which, after 1979, accelerated closures and privatisation of shipyards. A 1988 parliamentary review noted, “employment in merchant shipbuilding fell from 45,200 in 1977 to 11,300 in 1987, a loss of nearly 34,000 jobs” (British Shipbuilders (Hansard, 14 December 1988)).

The global context was brutal, almost every Western country’s shipbuilding workforce shrank due to overcapacity, but the UK’s decline was among the steepest. Whole regions, such as Wearside, Clydeside & Belfast, lost an industry that had sustained them for generations. Here, neither Labour nor Tories found an answer, Labour’s subsidies in the ’70s failed to make yards competitive, and the Conservatives largely chose to wind down civilian shipbuilding in the ’80s rather than fight to reinvent it. By the 1990s, apart from naval warship construction for the Ministry of Defence, Britain had almost entirely quit building commercial ships.

Fishing

The story of Britain’s fishing industry is one of politics and geography as much as economics. In 1945, fleets from ports like Hull, Grimsby and Fleetwood roamed the seas, including rich distant waters near Iceland and Norway. Tens of thousands of Britons worked as fishermen. But post-war treaties and maritime disputes, the Cod Wars with Iceland in the 1970s, saw Britain lose access to traditional fishing grounds.

The 1970s also brought the EEC’s Common Fisheries Policy, which imposed quotas on British boats while opening UK waters to European fleets. The combined impact was devastating. In 1970, roughly ~20,000 fishermen were working in UK waters, not counting fish processing jobs, by the mid-1990s this had halved to about 10,000. Today, the number is around 11,000 total fishers in the UK, a small fraction of the workforce. For context, in 1948 there were an estimated 32,500 fisherman alone, without those employed in the support industries.

The collapse of the distant-water trawler industry after 1976, when Iceland’s 200-mile exclusion zone ended Hull’s deep-sea fishing, wiped out thousands of jobs almost overnight. Entire communities on the Humber and Mersey coasts were plunged into unemployment in the late ’70s. Neither party could “save” fishing, Labour couldn’t reverse the Cod Wars outcome, and the Conservatives chose to enter the European fisheries regime which many fishermen felt sold them out. Thus, another proud industry dwindled to insignificance on Westminster’s watch. Neither party had managed to negotiate a solution with the other nations involved, more mismanagement.

The Merchant Navy – the sad decline of a behemoth

In 1945, despite the immense toll taken by World War II, Britain still commanded one of the most formidable merchant fleets the world had ever seen. According to Lloyd’s Fleet Review (1949/150), the United Kingdom, including Northern Ireland, maintained an impressive merchant fleet totalling approximately 17.0 million gross registered tons (GRT), with an additional 3.2 million GRT registered in the Commonwealth countries. By 1949, this fleet had not only replaced most of the tonnage lost during the war — which amounted to over 11.7 million GRT — but had grown by more than 1.049 million GRT above pre-war levels.

At its post-war peak, the British Merchant Navy was the second largest in the world, accounting for about 23% of the global merchant shipping tonnage. Only the United States surpassed it, owing to its vast wartime shipbuilding efforts that had seen the creation of thousands of Liberty and Victory ships under programs like the Emergency Shipbuilding Program.

In 1945, the Merchant Navy employed over 200,000 British residents — a vital workforce supporting not only global trade but also the post-war reconstruction efforts. By contrast, as of 2023, that number has dwindled to just over 24,000. While part of this decline is attributable to technological progress and automation, with modern cargo ships requiring smaller crews, it also reflects the precipitous collapse of Britain’s merchant shipping sector.

The reasons for this collapse are many, but a throughline in the story is the near-total absence of consistent and strategic government support.

A Vital Industry, Neglected by Successive Governments

In the immediate post-war years, Britain still saw shipping as vital to its economy, but this recognition did not translate into long-term policy. The Merchant Navy, unlike the Royal Navy or other arms of the state, received little sustained support. While other nations — notably Japan, Norway, and later South Korea — invested heavily in maintaining competitive merchant fleets, British policymakers largely took the Merchant Navy for granted.

This neglect was emblematic of a wider trend: successive UK governments, from both sides of the political divide, failed to recognise the strategic value of maintaining a strong national shipping capability. In the rush to modernise and liberalise the economy, shipping, like coal, steel, and shipbuilding, was seen as a declining legacy of empire rather than a cornerstone of future trade.

From the 1960s through the 1980s, the British fleet shrank dramatically. Government responses were piecemeal at best. There were no major subsidy schemes, no long-term investment in maritime infrastructure, and no strong effort to prevent the mass exodus of ships to flags of convenience. Shipowners, seeking lower costs and looser regulation, moved their fleets offshore. Rather than confront this trend or mitigate its effects, governments stood by, often citing the free market as justification for inaction.

The Merchant Navy was not nationalised like British Rail or British Steel, but its fate mirrored that of other key industries: a slow, painful decline brought about by global competition and domestic policy indifference. Maritime training colleges were shuttered or downsized, shipping firms consolidated or disappeared, and the vital link between merchant shipping and national capability was severed.

Attempts at Revival, Too Little Too Late

In 2000, the introduction of the UK Tonnage Tax scheme was meant to revitalise the sector by offering tax incentives to shipowners registering under the UK flag and employing British officers. While this saw a modest increase in UK-flagged tonnage and supported some maritime training initiatives, it was far from sufficient to reverse the damage of the previous decades. The global shipping industry had changed, and Britain had long since ceded its leadership.

The absence of a long-term maritime industrial strategy meant that the Merchant Navy was left to weather storms it could not survive alone, globalisation, deregulation, and aggressive competition from countries with far more supportive government policies.

The Legacy of Neglect

Today, the UK-flagged merchant fleet ranks well outside the global top ten. British-owned shipping firms still exist, many operating through subsidiaries abroad with multinational crews and foreign flagged vessels, but the Merchant Navy, once the envy of the world, has been reduced to a shadow of its former self.

The decline of the British Merchant Navy is more than just an economic story, it is a political one, reflecting decades of policy missteps and neglect. It is a story of a nation that once ruled the waves but allowed one of its most strategic industries to wither on the vine. The consequences of that neglect are still being felt today, in diminished maritime expertise, reduced national resilience, and the loss of a once-proud maritime heritage.

The UK is no longer self sufficient in many respects, the Merchant fleet used to keep the country alive, some 32,000 merchant sailors, from the UK, alone died between 1939 and 1945 ensuring the survival of the home nations, we lost some 54% (11.4 million GRT) of the entire Merchant fleet to enemy action, should the world see a major global conflagrations again, how will Britain sustain itself without the Merchant fleet, without the trained, experienced and brave souls of the Merchant Marine, the nations risks withering and dying. The decline of the Merchant Navy, like so many other industries in the UK, is one of criminal neglect by successive governments who failed to see how vital it is to the national economy, the strategic survival of the nation and also a symbol of national pride.

Railways and Automotive – Restructuring and Foreign Takeovers

Railways

Britain’s rail network, once part of our national pride that we had exported to other countries, nationalised as British Railways in 1948, also underwent dramatic job cuts. When first nationalised, over 600,000 workers staffed the railways (British Transport Commission – Hansard – UK Parliament) (Britain – Rail renationalisation: for whom? | Internationalistische Kommunistische Vereinigung). But as Figure 1 earlier indicated (with coal), the rail sector too saw waves of redundancies, particularly after Dr. Beeching’s 1963 disastrous and myopic plan recommended closing fully a third of the rail routes to curb losses. No-one in Parliament saw the railways as a strategic national asset that needed protecting.

By 1974, British Rail’s workforce was down to 256,000 (Britain – Rail renationalisation: for whom? | Internationalistische Kommunistische Vereinigung), implying roughly 350,000 jobs lost since 1948. It is telling that the majority of those cuts occurred under Conservative governments of the 1950s–60s, which accepted Beeching’s drastic rationalisation. Yet Labour is not blameless, the Wilson government (1964–70) closed around 60% of the lines Beeching slated, despite initial resistance. All told, the railways transformed from one of the largest employers in mid-century to a much leaner operation. By 1990, BR had under 150,000 staff, by the time of privatisation in the 1990s, around 100,000.

The irony is that while both parties cut rail jobs to improve efficiency, neither invested enough in modernising services, they tinkered around the edges and hoped for the best, but this led to chronic underperformance and public dissatisfaction. The eventual privatisation in the 1990s, a Conservative policy, broke British Rail into private franchises but created new problems of fragmentation. In sum, rail policy was a bi-partisan disappointment, waves of cuts and reorganisations, but no coherent long-term strategy to deliver the modern, reliable railway Britain needed then and needs even more now.

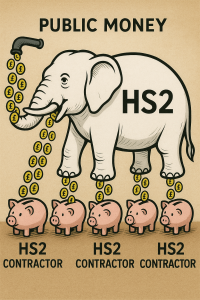

HS2 – The White Elephant That Britain Didn’t Need created from the hubris of Government.

HS2 (High Speed Two) was conceived as Britain’s grand answer to congested railways, regional inequality, and sluggish intercity travel. A high-speed rail line linking London with Birmingham, Manchester, and Leeds, it was heralded as a transformative project that would boost economic growth, modernise infrastructure, and “level up” the North. But since its inception in the late 2000s, HS2 has spiralled into one of the most controversial and costly infrastructure projects in British history, a textbook case of poor planning, political hubris, mismanagement of public funds and misdirected priorities.

Origins and Evolution

The idea for HS2 emerged under the Labour government in 2009 as part of a broader strategy to modernise Britain’s railways and reduce north-south economic disparities. The plan called for a Y-shaped network.

- Phase 1 would connect London Euston to Birmingham.

- Phase 2a would extend to Crewe.

- Phase 2b would branch out to Manchester and Leeds.

Trains would travel at up to 250mph, faster than anything currently running in the UK, and slash journey times by up to 40%.

At first, it sounded like a bold, forward-thinking project. But the cracks began to show quickly. Costs were dramatically underestimated. The original £33 billion estimate has now ballooned to, potentially, over £100 billion, making HS2 the most expensive high-speed rail project per mile in the world. Timeframes slipped repeatedly, environmental damage mounted, and crucially, public support began to evaporate.

A Project Few Wanted

Despite the PR campaigns, HS2 has never commanded widespread public support. Polls have shown that a majority of the British public either oppose the project or are indifferent to it. For many, the promise of shaving 20–30 minutes off a journey between major cities felt like a luxury they would never personally benefit from. Meanwhile, entire communities were disrupted, ancient woodlands destroyed, and countryside disfigured, all for a project that, by its own government assessments, offered low to moderate economic returns.

What was pitched as a national project increasingly looked like a London-centric vanity scheme. The key beneficiaries were affluent business travellers who already had decent transport links, while smaller towns and regions, particularly in the North and Midlands, saw little to no advantage. The business case for HS2 rested on outdated assumptions about commuter behaviour, pre-pandemic travel patterns, and questionable economic modelling that valued time savings over meaningful connectivity.

Better Spent Elsewhere

Perhaps the most damning critique of HS2 is not just its exorbitant cost, but the opportunity cost. Britain’s rail network, outside of a few main lines, is badly in need of investment. Northern cities suffer from unreliable and overcrowded commuter trains, outdated signalling, and under-electrified routes. Local journeys, those that matter most to people’s daily lives, are often slow, patchy, and poorly integrated.

Had the tens of billions sunk into HS2 been invested in regional rail improvements, the benefits would have been immediate and widespread. Projects like Northern Powerhouse Rail, upgrades to the TransPennine line, electrification of secondary routes, station modernisation, and reopening of mothballed branch lines would have delivered real value across the country that would have positively impacted lives, business and the national economy. Instead, billions have been spent on tunnelling under the Chilterns and buying up swathes of property along the HS2 corridor.

Even within London and the Southeast, where much of the money has gone, HS2 will do little to relieve commuter pressure or integrate with existing networks. The planned connection to Euston, for instance, has been mired in delays and may never be completed without additional funding. Meanwhile, the crucial eastern leg to Leeds has been scrapped entirely, stripping the project of one of its core goals.

Economic Mirage

HS2 was sold as an engine of economic renewal, an infrastructure equivalent of the post-war motorway boom. But real economic transformation doesn’t come from faster travel between cities, it comes from better connectivity within them. Faster trains to London do not decentralise growth, they can actually accelerate brain-drain, drawing skilled workers further toward the capital. Independent analyses, including those from the National Audit Office and Transport Select Committee, have repeatedly raised doubts about HS2’s economic case.

Moreover, the pandemic has permanently altered commuting and business travel habits. The rise of remote work and digital meetings has diminished the need for frequent intercity travel. The world has changed, but HS2 hasn’t. It continues to barrel forward, decades behind reality, fuelled by sunk costs, political hubris and inertia.

A Monument to Mismanagement

As of 2024, large portions of the HS2 network have been cancelled. Only the London-to-Birmingham section, Phase 1, is under active construction. The rest has either been indefinitely delayed or axed altogether. Yet the spending continues, and the disruption lingers. What remains is an over-budget, under-delivering partial line that will serve a narrow slice of the population, with little hope of delivering its once-promised transformation.

HS2 may one day become a cautionary tale taught in planning and economics classrooms, a grand project born of good intentions via rose tinted glasses, undone by political mismanagement, inflated promises, and a failure to respond to changing national needs.

In truth, Britain never needed HS2. It needed better railways, one that worked for everyone, not just a few. What it got instead is a white elephant: impressive in scale, expensive in upkeep, and fundamentally misplaced.

Automotive

The car industry exemplifies mismanagement on the industrial shop floor. In the 1960s, the UK was the world’s second-largest car producer. At its peak, over one million Britons were employed in making cars and components, about 5% of the national workforce ( How the UK Lost its Car Manufacturing Industry – CBS News).

British brands like Austin, Morris, Vauxhall, Jaguar, Land Rover and Leyland dominated the home market and were decent sized players in several foreign markets. Yet by the late 1970s, British Leyland, the conglomerate comprising most domestic carmakers, was in such dire straits that it was nationalised in 1975 to save it from bankruptcy.

What went wrong? Put simply, bad management, government indifference and militant labour relations.

Through the 1960s and ’70s, UK car plants became infamous for low productivity, poor build quality and constant strikes. “Output at overmanned plants was hit by constant labour disputes from the 1950s,” and management “proved slow to adapt to changing markets” ( How the UK Lost its Car Manufacturing Industry – CBS News).

Foreign rivals, especially from Germany and Japan, produced better-quality cars more efficiently, eroding British exports. Both Labour and Conservative governments meddled, urging mergers to form a national champion, the creation of British Leyland in 1968 was backed by Wilson’s government, then pumping in public money when BL imploded financially in the mid-’70s.

Labour’s instinct was to bail out the failing carmaker, as Industry Minister Tony Benn did with a huge rescue package in 1975, rather than let market forces play out. This kept an ailing company alive, but did not cure its ills or solve the majority of its problems, they simply threw public money at the wall and hoped it stuck, however, BL continued losing money and shedding jobs through the late ’70s and early ’80s.

The employment numbers tell the story. British Leyland alone employed nearly 200,000 people in the 1960s ( How the UK Lost its Car Manufacturing Industry – CBS News). By 1988, after successive layoffs and factory closures, BL (renamed Rover Group) had under 50,000 employees.

Virtually all the famous British marques ended up either discontinued or sold to foreign owners in the 1980s–90s, Jaguar to Ford, Rolls-Royce/Bentley split between Volkswagen and BMW, Mini and Rover and Land Rover (Initially) to BMW.

Today, the UK car industry is foreign-owned and employs around 168,000 in manufacturing, with another ~800,000 in supply and retail (Automotive industry in the United Kingdom – Wikipedia).

This is a significant drop in direct manufacturing jobs from the heyday. While the industry eventually improved its productivity under foreign management, the cost was Britain’s loss of ownership and control. Successive governments failed to address the root causes, poor management-union relations, build quality and underinvestment in new models, until it was too late.

By propping up British Leyland in the 1970s for political reasons, the government only delayed a reckoning, when privatisation and foreign takeover finally came under the Conservatives, tens of thousands of additional jobs were cut to return the companies to viability.

In aggregate, Britain’s share of global manufacturing output fell from 25% in 1950 to under 10% by the 2000s. Major industries that employed roughly 40% of the workforce in 1945 shrank to under 14% by the 2010s (The Long Shadow of Job Loss: Britain’s Older Industrial Towns in …).

The deindustrialisation of Britain stands as an indictment of poor stewardship by both parties, Labour’s aggressive state-socialist experiments largely failed, and the Conservatives’ belated market-oriented corrections were often cold and abrupt, without regard for social consequences or rebuilding for the future. Neither party truly succeeded in crafting a sustainable industrial strategy to keep Britain competitive as the world changed and neither can claim to have the moral high ground.

Unions and Governments – Power, Patronage, and Payoffs

No analysis of Britain’s post-war economic woes can ignore the outsized role of trade unions, and Labour’s intimate relationship with them. Unions were a major force in British industry and, crucially, the primary funders of the Labour Party. This close linkage often created conflicts of interest when Labour was in power, as union demands could carry more weight than the broader economic good.

We should be careful to note that Trade Unions, managed intelligently, without any political agenda and the best interests of their members and their employer at heart, are a boon to any industry and economy, if they work hand in hand they can improve workers interests, productivity and quality of work, all of which create a loyal workforce that works WITH management not opposed to them – but the management requires real leadership too, no matter how good a Union is, if the management are narcissistic, indifferent or just inept, the relationship will fall apart and create the “them and us” attitude seen all too often.

From the 1940s through the 1970s, Labour was effectively bankrolled by the unions. Up to 90% of Labour Party income came from trade union affiliation fees in the early 1980s (Unions review links with ‘new Labour’ | European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions). Even by 1995, it was 50% (Unions review links with ‘new Labour’ | European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions).) The unions literally “created” Labour and expected influence in return (Unions review links with ‘new Labour’ | European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions) (Unions review links with ‘new Labour’ | European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions).

When Labour governments faced union pay demands or strikes, they were thus in a bind, yielding would fuel accusations of union influence and control, but resisting could mean biting the hand that fed them, with the industrial chaos that was sure to follow.

More often than not, Labour chose to appease the unions with generous concessions, putting political expediency ahead of national interests at the long-term expense of the economy.

A prime example is the 1974–75 miners’ pay deals. After Heath’s Conservative government fell in early 1974 amid a coal miners’ strike, the incoming Labour government of Harold Wilson moved swiftly to reward the NUM. “The new Labour government increased miners’ wages by a whopping 35% immediately after the February 1974 election”, and in February 1975 granted a yet another 35% raise with no new strike (Three-Day Week – Wikipedia).

These astonishing pay hikes far outpaced inflation and productivity. The NUM had effectively won a jackpot, union leader Joe Gormley exulted that “the miners hit the jackpot” with Wilson’s deal (Tides of History on X: “#OTD 1974. Harold Wilson ends coal strike …).

It was a political payoff for the union’s role in unseating the Tories. But it came at a cost: it sent a signal to all unions that militancy would be richly rewarded under Labour. Indeed, through the 1970s, other unions pushed for similar big rises, contributing to the wage-price spiral that fuelled Britain’s high inflation.

By 1975, inflation had hit 25%, partially due to such wage settlements. Labour tried to rein it in with a “Social Contract”, voluntary wage restraint in exchange for social reforms, but by 1978 unions had lost patience with government inaction and broken promises and the wave of strikes known as the Winter of Discontent (1978–79) crippled the country, rubbish uncollected, hospitals picketed, even graves left undug.

Labour’s close union ties, which had earlier led them to lavish pay increases on public employees, now hamstrung the government’s attempt to enforce pay discipline. The paradoxical result – the Labour government that had been put into power by Union action and the indulgent pay rises to unions ended up being brought down by those very same unions with the national strikes in 1979, returning a Conservative Government under Margaret Thatcher.

Labour’s union appeasement was not limited to wages. Unions also expected a friendly legislative environment. In 1969, the Wilson government flirted with union reform via Barbara Castle’s “In Place of Strife” proposals, which would have introduced cooling-off periods and strike ballots. But Labour’s own union backers rebelled vehemently, and the government backed down, dropping the reform.

A decade later, during 1974–79, Labour repealed the Conservatives’ 1971 Industrial Relations Act, which unions hated and generally restored a pro-union legal regime. These moves pleased Labour’s paymasters but arguably perpetuated Britain’s strike-happy industrial culture, undermining productivity and the country’s image as a stable place to do business, which severally limited investment.

Crucially, the flow of money from unions to Labour was enormous. In 1980, some 7.7 million trade union members paid the political levy to Labour-affiliated unions (Unions review links with ‘new Labour’ | European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions) (Unions review links with ‘new Labour’ | European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions), generating funding that constituted the bulk of Labour’s coffers. As one review noted, “throughout the 1970s and 1980s, [union] affiliation fees accounted for just over 80%” of Labour’s funding (Unions review links with ‘new Labour’ | European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions).

This financial dependency helps explain many of Labour’s choices. When faced with strikes in core donor unions, Labour governments often reached for the public cheque book. For instance, after the fire-fighters’ strike of 1977, the Labour government approved a hefty pay rise for them too.

When public sector unions struck, Labour tended to settle generously. While this secured Labour a reputation as the workers’ friend, it also ballooned the public payroll and budget, often without corresponding gains in service delivery. It is telling that by 1979, even amid improved pay, the public experienced one of the worst breakdowns in services due to strikes, a sign that the union appeasement strategy had failed to guarantee industrial peace, and the Unions were out of control.

On the Conservative side, union relations were adversarial, peaking with Thatcher’s confrontation with the NUM and her subsequent union reforms. Thatcher came in determined to curb union power which she saw as an impediment to economic progress.

The Conservative approach (post-1979) was to legislate, banning secondary picketing, requiring secret ballots for strikes, ending the closed shop, etc. Over the 1980s, these laws dramatically weakened trade unions, union membership fell by half, from ~13 million in 1979 to ~7 million by the mid-1990s.

One could argue this was necessary after the excesses of the 1970s. But here is the tragedy, had earlier governments, including 1960s–70s Labour, managed unions more firmly but fairly, balancing genuine worker protections with accountability, the drastic clampdown of the 1980s might not have been needed.

Instead, Labour allowed unions to grow so dominant, with seats on nationalised industry boards, and a direct line into Downing Street, that by the late ’70s one could be forgiven for thinking the Unions ran the country.

This provoked the Thatcherite backlash which, while restoring management’s prerogative, arguably swung the pendulum too far back the other way, eroding workers’ voice and contributing to today’s insecure labour climate.

In summary, the interplay of unions and government in post-war Britain was often unhealthy. Labour, financially reliant on unions, too often ceded economic control to them, to the detriment of competitiveness and effective governance.

The Conservatives, in over reaction, often took a punitive stance that, while solving some immediate problems, taming inflation & ending crippling strikes, left social wounds.

For instance, Thatcher’s defeat of the miners’ strike in 1985 broke the back of union militancy, but it also left mining communities feeling deliberately shattered. Thatcher’s own memoir noted the need to show that the unions were defeated and “rejected by their own people”.

There was a lack of balance, Labour backed down and the Tories cracked down. There was no consistency to fix problems, neither found a collaborative middle path for constructive industrial relations. Thus, union power went from unaccountable to negligible, neither extreme is conducive to a healthy economy or society.

Conservatives in Power – Failing to Reverse Labour’s Damage – and Piling on their Own.

It would be a mistake to lay Britain’s decline solely at Labour’s feet. The Conservatives had ample spells in government, a majority of years since 1945, and repeatedly failed to fundamentally reverse or repair Labour’s structural damage.

In some cases, Tory governments even expanded the state’s role, contrary to their free-market rhetoric, or simply enjoyed short-term gains while neglecting long-term investment, another form of mismanagement by omission.

The Post-War Consensus

After Attlee’s massive nationalisations, one might expect subsequent Conservative governments, Churchill, Eden, Macmillan in the 1950s, to roll them back. But they did not.

Instead, the Tories broadly accepted what came to be called the “post-war consensus”, maintaining a mixed economy and welfare state. In 1947, the Conservative Party’s own policy charter pledged not to reverse Labour’s reforms (Post-war consensus – Wikipedia).

Indeed, “the Conservative Party accepted many of these changes”, boasting even that they could run the nationalised NHS better (Post-war consensus – Wikipedia). Apart from reprivatising the steel industry in 1953 and denationalising road haulage, the 1951–64 Tory governments left the bulk of Labour’s state-owned apparatus intact (Nationalisation).

This was a political calculation – the public, having experienced full employment and social support, liked the new status quo. Conservative leaders like Harold Macmillan embraced a paternalistic One-Nation conservatism, famously, and cynically, saying Britons had “never had it so good” under rising living standards, partly enabled by Keynesian state intervention.

However, the failure to reverse nationalisation meant that all the latent problems in those industries, as described earlier, were allowed to fester. The Conservatives essentially kicked the can down the road through the 1950s–60s. By the time they confronted those issues under Maggie Thatcher in the 1980s, the problems were far worse and the impact of reform nothing short of catastrophic for many tens of thousands of British workers.

Lack of Industrial Strategy

While Labour’s error was over intervention, the Conservatives’ error was often under-intervention when it actually mattered. A prime example is British Leyland. The Heath government in 1971 initially took a hands off approach as BL visibly and publicly spiralled, but when the company verged on collapse in 1974, even the Conservative cabinet agreed to an emergency state loan, the “Chrysler bailout” similarly saw Tory help for another carmaker.

In other words, the Conservatives too succumbed to use public funds to rescue failing companies, just as Labour would do more openly. Yet these rescues came without a coherent long-term plan to fix the underlying issues. Similarly, in shipbuilding, the Heath government created intervention funds to subsidise ship orders in 1972, delaying the reckoning by a few years, making the impact harder and recovery all but impossible.

The Heath U-Turn

In fact, Edward Heath’s 1970–74 Conservative government is a study in inconsistency. Elected on a free-market manifesto, Heath initially tried to cut state support and tame unions – only to perform a spectacular U-turn in 1972 after unemployment spiked and confrontations, like the national miners’ strike, mounted.

Heath ended up nationalising Rolls-Royce in 1971, to prevent its bankruptcy, a Conservative PM nationalising a major company! imposing wage and price controls by 1972 and infamously declaring “we are all Keynesians now.”

This retreat undermined any chance of reversing Labour’s structural policies, if anything, Heath added fuel to the fire by adding new layers of intervention. By 1974, the state’s role in industry was as heavy as ever, but without the social consensus Labour enjoyed, a worst of both worlds scenario that damaged the Conservatives’ economic credibility.

Failure to Protect Strategic Industries

The Conservatives also failed to proactively support industries that genuinely needed strategic help to transition. They tended to rely on market forces, which often meant allowing industries to decline abruptly. For example, no serious industrial regeneration plans were implemented for areas losing coal and steel jobs in the 1980s. Thatcher’s government, while right to cut deadweight industries, adopted a sink-or-swim approach for communities, and sink many of them did.

£Billions flowed from North Sea oil revenues in the 1980s, but relatively little was ever reinvested into modernising British infrastructure or manufacturing, instead, much went to fund unemployment benefits and tax cuts. Unlike Norway that created a Sovereign Wealth Fund with its Oil money.

In hindsight, the Thatcher era squandered an opportunity to use a one-off windfall (oil) to reshape the economy for the future, such as invest in high-tech & education. The laissez-faire stance meant no replacement industries arose in many areas, leaving lasting regional inequality.

The Thatcher and Major governments also allowed short-term financial interests to dominate, “profit now, invest later”, which contributed to deindustrialisation. By the 1990s, Britain was increasingly reliant on the service sector, especially finance in London, while manufacturing withered and Britain fast became a “has been” of industrial potential.

Finally, consider defence and infrastructure, domains typically seen as Conservative strengths. Yet, as we examine next, even these were subject to penny-pinching and neglect under both parties, including the Tories.

Conservative governments from the 1990s onward were quick to cut defence budgets the “peace dividend” after the Cold War, that is now biting us in the arse, and often delayed critical infrastructure upgrades, such as rail modernisation which was sluggish even in the boom of the 1980s.

In short, the Conservatives can be faulted not only for the social harshness of some of their remedies, but for lack of foresight and follow-through. They often won short-term gains, taming inflation & boosting the City of London, at the cost of long-term resilience due to a loss of balanced growth coupled with regional decay.

If Labour often overspent and underdelivered, the Tories often underinvested and pretended market forces alone would deliver. Both approaches failed to secure a sustainable economic foundation. Delusional governance simply does not work, no matter the chosen delusion.

Undermining Defence – Decades of Declining Military Investment

Beyond economics, successive governments also eroded Britain’s hard power through continual defence cuts. Once a world-straddling military power, the UK steadily scaled back defence expenditure after 1945, often for understandable reasons such as the rightful end of empire and postwar budget pressures, but arguably to excess. The result is a considerably diminished defence capability today, raising questions about the UK’s ability to meet international obligations. Or even defend its own beaches, skies and waters.

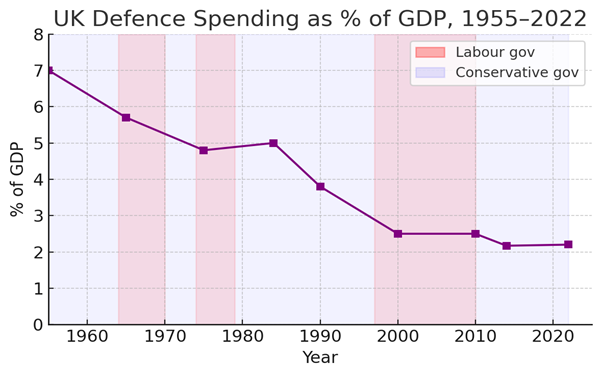

Figure 3: UK Defence Spending as a percentage of GDP, 1955–2022. Red = Labour, Blue = Conservative. Defence outlays fell from ~7% of GDP in the 1950s to around 2% today (House of Commons – Shifting the goalposts? Defence expenditure and the 2% pledge – Defence Committee) (300 years of UK public finance data).

At the close of World War II, defence spending was astronomically high (over 40% of GDP in 1945) (300 years of UK public finance data).

Demobilisation naturally brought this down, but by the mid-1950s, amid Cold War tensions and the Korean War, the UK still spent around 7% of GDP on defence (1955–56) (House of Commons – Shifting the goalposts? Defence expenditure and the 2% pledge – Defence Committee).

This was a substantial commitment, reflecting Britain’s role as a leading NATO power. However, from that peak, it’s been steady downhill. By the 1960s, defence dipped to ~5–6% of GDP (Charts of Past Spending – UkPublicSpending.co.uk).

In the 1970s, it hovered around 4–5%. After the Cold War’s end (1990), it plunged under 4%, reaching 2.3% by 2013 (House of Commons – Shifting the goalposts? Defence expenditure and the 2% pledge – Defence Committee) (House of Commons – Shifting the goalposts? Defence expenditure and the 2% pledge – Defence Committee), barely meeting NATO’s recommended minimum.

Today it sits roughly at 2.1–2.3% (House of Commons – Shifting the goalposts? Defence expenditure and the 2% pledge – Defence Committee) and risks falling below 2% without new funding. The current Labour Government has promised increases as Europe is faced with an unreliable US ally and the looming threat of conflict with Putin’s Russia, whether this is just political hot air or manoeuvring we will have to wait and see.

This relentless decline (illustrated in Figure 3) occurred under both parties.

Conservative governments often led the biggest drawdowns – for instance, the 1957 Sandys Review under a Tory government slashed conventional forces (in favour of nuclear deterrent) and closed bases east of Suez, cutting expenditures.

In the 1990s, it was the Conservatives, under John Major, who executed the “Options for Change” review post-Cold War, cutting manpower by ~20%. Labour in the 1970s also made deep cuts, the 1975 defence review scrapped a planned new aircraft carrier, for example. And New Labour in the 2000s, despite committing UK Forces to heavy combat operations in Afghanistan & Iraq, did not markedly increase the share of GDP for defence, leading to chronic strains on personnel and equipment.

By 2015, senior military figures were warning that Britain’s ability to field a full-spectrum force was in jeopardy. The House of Commons Defence Committee noted the “historic level” of decline – from ~7% of GDP in the 1950s to barely 2% now (300 years of UK public finance data) (House of Commons – Shifting the goalposts? Defence expenditure and the 2% pledge – Defence Committee).

Each tranche of cuts was justified by governments as “right-sizing” for the threats of the day or harvesting a “peace dividend”. Yet cumulatively, they left the UK with aging equipment, reduced readiness, and dependence on allies. For example, the Royal Navy went from over 50 destroyers/frigates in the 1970s to just 19 today; the British Army from over 150,000 troops during the Cold War to around 80,000 now; the Royal Air Force from 850 combat aircraft in the 1960s to under 150 today.

Of course, defence needs evolved, costly nuclear weapons, decided on by political hubris and pressure from the Americans who supplied them, replaced many conventional forces, and efficiency improved with technology. But arguably both parties neglected long-term defence planning in pursuit of short-term savings. The 2010 SDSR (Strategic Defence Review) by the Conservative–LibDem coalition imposed an 8% real terms cut, leading to, infamously, a period where Britain had no operational aircraft carriers (2010–2018) and scrapped the Nimrod maritime patrol planes with no replacement, creating a capability gap. Controversially, the almost overnight scrapping of the RAF/RN Harrier fleet cost and estimated 12,000 jobs and allegedly saved the MoD about £900 million over 8 years – The 2015 Strategic Defence and Security Review confirmed the UK’s intention to buy 138 Lightnings and subsequent work has seen a massive infrastructure upgrade at RAF Marham, the type’s RAF/Royal Navy main operating base, thus, all savings from scrapping Harrier are questionable.

These decisions reflected a Treasury-driven mentality, treat defence as just another discretionary spend to trim. Such thinking has roots in the 1960s Labour government (Denis Healey’s cuts) and carries on. The net effect is Britain punching below its weight relative to its economy size. As recently as the 1980s, Britain spent ~5% GDP on defence, during the Falklands conflict era, 1984 defence was 5.5% (UK defence spending GDP share 2024 – Statista)); by 2015 it was less than half that (House of Commons – Shifting the goalposts? Defence expenditure and the 2% pledge – Defence Committee).

In strategic terms, this decline limits Britain’s global influence. While every government pledged commitment to the armed forces, most failed to fund those commitments adequately. The armed forces often had to do “more with less,” political speak for penny pinching, resulting in overstretch in Iraq & Afghanistan deployments without proper kit, leading to equipment shortages and avoidable casualties that sparked public outcry.

So, just as with industry, successive governments took an axe to defence in a gradual, piecemeal way, never candidly debating Britain’s role in the world or aligning resources to strategy.

The consensus to cut was bipartisan – the damage to military capability, and Britain strategic credibility was indisputable.

It exemplifies the broader theme – politically motivated short term fixes, ill thought budget cuts, failure to provide the MoD with a strategic vision and the total undermining of the UK long-term strength, even damaging the UK ability to the basic ability to defend itself.

This also damaged another aspect of Britain’s industrial base, the Defence Industrial base that, over the decades, has seen jobs decimated and the UK reliant on foreign producers of equipment, even the Royal Small Arms Factories, a mainstay for hundreds of years, were closed for short sighted and short term political gain, with no thought of how they would impact jobs, lives and the military. Britian, today, can barely manufacture water pistols let alone weapons for the defence of the nation.

The NHS Today – Funding Surges, Bureaucratic Chaos, and Mixed Outcomes

We return finally to the NHS, the emblem of Britain’s welfare state. While Labour likes to say, “we built the NHS,” both parties have struggled to fund and manage it effectively in the decades since. The NHS has grown to become one of the world’s largest employers, and its budget has skyrocketed, yet it perennially faces crises of morale, waiting times, and outcomes.

Funding Trends

Overall, NHS funding, inflation-adjusted, contrary to what many commentators claim, has inexorably risen under every government.

Health spending was about 3% of GDP in the 1950s; it reached 9% of GDP by 2022 (300 years of UK public finance data). Every Prime Minister claims to “spend more on the NHS than ever before” – and usually that’s true in absolute terms. But the rate of increase has varied sharply by party. Historically, Labour governments have increased NHS funding faster than Conservatives. Notably, the 1997–2010 Labour government doubled NHS spending in real terms. Tony Blair’s pledge to raise health spending to the European average saw annual increases of ~6% for many years (The NHS Budget And How It Has Changed | The King’s Fund).

By the mid-2000s, the NHS budget reached £100 billion (treble the 1997 level) ( NHS: the Blair years – PMC ). This infusion did produce results, waiting lists and times fell dramatically in the 2000s. In 1997, a quarter million patients waited over 6 months for surgery ( NHS: the Blair years – PMC ); by 2007, only 199 patients waited that long – effectively eliminating the dreaded six-month wait ( NHS: the Blair years – PMC ). Average waits fell to 6.6 weeks ( NHS: the Blair years – PMC ), near unheard of levels, and 98.5% of A&E patients were seen within 4 hours by 2006 ( NHS: the Blair years – PMC ), up from 75% in 2003 ( NHS: the Blair years – PMC ).

These improvements, achieved under Labour’s funding boom, show what money can do. They also implemented targets and reforms, some controversial, like private treatment centres and GP fundholding, that arguably helped drive better performance.

However, Labour’s NHS record wasn’t spotless. The 2000s increases, while cutting waits, came with much waste and bureaucracy. The period saw a proliferation of managers and administrators, by 2010, critics pointed out that despite huge spending, the NHS was hitting diminishing returns, productivity in health care actually fell in the early 2000s even as budgets rose.

Scandals like Mid Staffs, where appalling care was delivered in pursuit of targets, dented Labour’s reputation. By 2010, despite unparalleled funding, public satisfaction was oddly mixed, a paradox Polly Toynbee dubbed “results have never been so good, yet the public view… never so glum” ( NHS: the Blair years – PMC ).

Then came the 2010 Conservative-led government, which imposed austerity. From 2010 to 2019, NHS spending growth slowed to ~1% per year on average, the slowest decade of growth in NHS history (The NHS Budget And How It Has Changed | The King’s Fund). During this time, demand, an aging population, and other pressures, kept rising, so the system began to creak again. By the mid-2010s, waiting times started climbing once more. The 4-hour A&E target, consistently met under Labour by 2005–2010, was missed increasingly after 2013 and has not been met nationally since 2016 (NHS key statistics: England – House of Commons Library).

Today, as of 2023–24, the NHS England waiting list stands at 7.5 million patients – an all-time high (NHS key statistics: England – House of Commons Library).

Nearly 40–50% of A&E patients wait over 4 hours in winter, far worse than the <5% figure a decade earlier (NHS key statistics: England – House of Commons Library).

The Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated these issues, but underlying trends were negative even before 2020. The Conservative approach included a top-down reorganisation in 2012 (Andrew Lansley’s disastrous and damaging Health and Social Care Act) that consumed energy on structural changes widely viewed as botched. Frontline staff numbers did rise, more doctors and nurses added in 2010s, albeit not fast enough, but funding did not keep up with the growing needs. Thus, under Conservative stewardship, the NHS has slipped back into crisis mode, with record deficits in hospital trusts, staff strikes over pay, and performance measures the worst in decades. It’s a far cry from the mid-2000s when ministers declared the NHS “saved” after Labour’s injection of cash.

In fairness, both parties face the same fundamental NHS challenge – how to finance ever-expanding healthcare demand in a tax-funded system. Labour tends to pour in money, and later worry about efficiency, whereas Tories tend to stress efficiency, then often end up injecting emergency cash when things collapse.

Neither has cracked the puzzle of long-term NHS sustainability. The result is a boom-bust cycle – one government’s cash boost yields short-lived improvements, the next government’s restraint sees decline, and so on. For example, under Labour by 2009, NHS England met virtually all cancer treatment targets; by the late 2010s under the Tories, cancer wait targets were routinely missed, with thousands waiting >62 days for treatment (NHS key statistics: England – House of Commons Library).

Now in 2025, both waiting lists and staff vacancy levels are at record highs (NHS key statistics: England – House of Commons Library), despite the government repeatedly announcing extra billions. Money has been thrown at the NHS wall hoping to plug holes and fix problems, rather than committing to a root and branch review of how best to serve the nation and use limited public money.